Stories

This article from our President appeared in the Clan Wardlaw Association

Newsletter Issue #7

From the Past-President’s Desk William F. (Bill) Wardlaw

SLAVE NARRATIVES: A SORROWFUL BUT RICH HISTORY

In the last newsletter, I mentioned my Great-great-grandfather, William Louis

Wardlaw. Born in South Carolina about 1815, he moved as a young boy to Alabama where grew up and married one Elizabeth Crawford and then relocated to Arkansas. In 1857 the family moved a final time

to Texas, settling near the Falls of the Brazos River. He died there in 1862 at about 47 years of age. Clearing and cultivating raw land in the mid-nineteenth century was no easy task and Lewis

had help in his dream of success. Like many Southerners of his day, Lewis Wardlaw was a slave owner.

A few years ago, The Marlin Democrat newspaper of Marlin Texas, reprinted a 1932

interview with former slave Nellie Wardlaw Smith, then about 91 years old. Her story is a fascinating piece of history that I think is both sad and greatly interesting. The following is a condensed

version of that interview and in her words:

“We settled about five miles from the Brazos and lived camp style until we could

build our houses. Some of the men cut down trees and cleared land while the women followed along and burned the brush. The best trees were used to make logs for the houses. As soon as the land was

cleared we planted corn and cotton.”

“My ole Massa (Louis Wardlaw) was a hard worker. He worked along in the field

beside us. We went to the field early in the morning. There was a black man to blow the horn to get the slaves up way ‘fore day. We worked from ‘fore daylight ‘till dark. I had my 400 pounds of

cotton to pick every day. Ole Massa whipped me once ‘cause I did not drop the corn right. I could not learn it right at first and he beat me good. Soon after that he sent me to the ‘big house’ to

help nurse the children and do some of the house work.”

“My ole Missus (Elizabeth Wardlaw) would weave and sew for the slaves. She carded

the cotton into rolls and spun it into yarn and reel the yarn into hanks. Ole Missus could weave about twelve yards of cloth in a day. We got two sets of clothing a year, one in the spring and one in

the fall. We had heavy underwear and did not get cold. Nearly all of our clothes were white. We had ‘Russett Brogans’ and ‘coarse’ shoes. Missus knitted stockings and socks for

us.”

“We did not know what a cook stove was in those days. We cooked on large

fireplaces. Some of them was large enough to use eight foot sticks of wood. There were iron cranes at each end. We hung pots on them and swung them back over the fire. You could not go off and leave

your dinner for fear a pot might turn over and spill your grub. We baked pretty, yellow pound cakes in the ovens that sat on legs over the fire. Taters baked in the ashes was hard to

beat.”

“We all went to (church) meeting under the brush arbor once a month. The

white people sat near the front and the black people in the back. We could not read nor write but we loved to hear (the preacher) read the Bible. Ole Massa would let us dance and have a good time

when the work was laid by. We had a man who could play the fiddle and we had a good time. Sometimes he (Louis Wardlaw) would give us a ‘black and white’ (a furlough pass) and let us go to the

adjoining plantation. If we did not have this paper the patrol would whip us and take us back home.”

“Ole Massa was getting ready to go enlist in the Confederate Army when he died.

We did not have any trouble during the war. One day John Wardlaw (one of Louis and Elizabeth’s older sons) called us all up to the house and told us we was just like him. We were free and we could

stay with him and he would pay us. We was lost like a chicken from his mammy. We stayed on with the Wardlaw family for a while and then we moved on Mr. Churchill Jones’

plantation.”

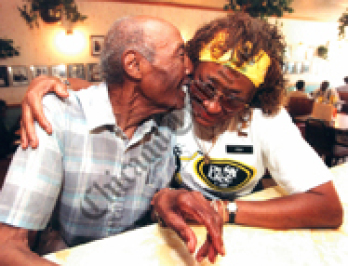

I know nothing of Nellie Smith’s life in the years just after the war but in

subsequent years came to be employed by my Great-grandfather N.J. Wardlaw, Sr. who had been only ten years old when the war ended. She stayed with the family for many years, even immigrating with

them to west Texas in the 1880s. Although about thirteen years his senior, she nursed N.J. in his final years. He died in 1931 at the age of 76. Nellie Wardlaw Smith was a remarkable woman with a

long life and a captivating story.

Company E, 4th United States Colored Infantry at Fort Lincoln, Washington, D.C. Library of Congress - Theirs was one of the detachments assigned to guard the nation’s capital.

By the end of the Civil War, roughly 179,000 black men (10% of the Union Army) served as soldiers in the U.S. Army and another 19,000 served in the Navy. Nearly 40,000 black soldiers died over the course of the war—30,000 of infection or disease. Black soldiers served in artillery and infantry and performed all noncombat support functions that sustain an army, as well. Black carpenters, chaplains, cooks, guards, laborers, nurses, scouts, spies, steamboat pilots, surgeons, and teamsters also contributed to the war cause. There were nearly 80 black commissioned officers. Black women, who could not formally join the Army, nonetheless served as nurses, spies, and scouts, the most famous being Harriet Tubman who scouted for the 2d South Carolina Volunteers.